They welcomed him with whoops and shouts.

Clapping all the while, as he made his way to them.

“welcome, welcome brother!”

He approached them slowly, shoulders slumping with each footfall.

They nodded to each other knowingly, then pressed forward towards him, closing the distance between them.

“Welcome, welcome!”

“Too soon, too soon” he muttered. “I had more words, more things to write, more things to say.”

“Ah, not to worry. You said all you needed to. All that had to be said, was said.”

“But I’m not sure they heard me. I was still writing, making the case again for them to center themselves…”

“They heard.” They re-joined patiently.

“But did they listen? Will they listen?” he said.

“That’s up to them now.” They said, surrounding him.

He looked up and around, a light of recognition sparking finally in his eyes.

“Oh” was all he could manage as his shoulders lightened.

Achebe, Awoonor, Maathai, Emecheta, Mandela, Wainaina, Bâ, Nsamenang, Hunter, Aidoo, Casely-Hayford, Laye…and there also, Du Bois, Nkrumah, Garvey, Angelou…

His smile had stretched to his ears.

“Welcome home” they said.

Flash fiction written in tribute to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, June 2025

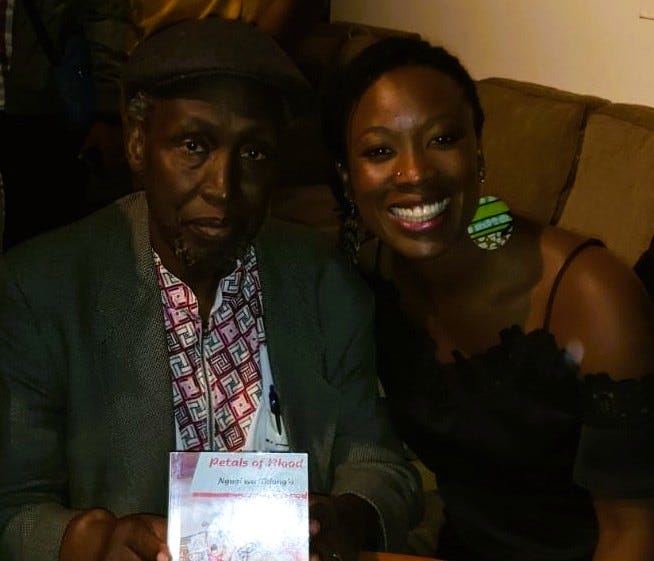

At Afrocentrism Conference in Vancouver, September 2019

I had all sorts of notes for this post, as always, from insightful conversations, meaningful moments and stories I had been part of over the past month.

Then I heard Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o died.

When I looked at my list of notes again, so much of it didn’t seem so meaningful or existential anymore. I experienced again, that shift in perspective that happens when someone that matters to you in some way passes on. I am not feeling the grief that comes with losing a close loved one, but I feel, every time I see another tribute, post or commentary about Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo, the way I felt when the external examiner for my doctoral dissertation Dr. A. Bami Nsamenang passed on in 2018. Dr. Nsamenang and I only corresponded by email and had precisely 2 telephone conversations. Yet, when years after I graduated, I googled him on a whim after I had not heard from him for a while and learned of his passing from public posts by several Psychological Associations, I was stunned and pensive for days. We had corresponded intermittently and had plans to one day meet in person. That day never arrived. Yet, I still read his work, quote him and build on his ideas in the pursuit of my own truths.

These humans, who I barely knew, have indelibly shaped my worldviews. So, more than anything, in the remarks and messages all around me as people note with inflections of disbelief that wa Thiongo has passed, I am holding a sense of wonder for how humans who barely know each other can be connected through thought and written word. I notice I am also holding the same panic I felt when my last paternal uncle passed on a few years ago. It hit me then, as it does now, that the generational baton is being passed on. And while so many of my notes and musings from the past month now seem trivial, one in particular stands out. The simple note in preparing for a workshop in which I was going to ask: What is story? This is a question Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o often asked Africans far and wide.

I met Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o only once, at the Afrocentrism Conference organized by students at Simon Fraser University and University of British Columbia in 2019. He was a keynote speaker and as a speaker and facilitator for various other segments, I got to meet him and spend a bit of time, sharing ideas and talking with him throughout the conference. Every tribute I have read notes his intellectual generosity and over the days of the conference, that was my experience too. I left every conversation with him challenged. It was Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o who made me realize, that the loss of my ethnic language meant I could only think within the bounds of English. This meant that without intentionally widening my lens, my capacity to understand my own heritage was limited by this gap.

Suddenly, an interaction I’d had with my friend and editor Njoki for my book Ancestries, which was launched at that very Afrocentrism conference, was further illuminated. During the editorial process, we had laughed about her notes on the very first line in my manuscript. I had described a brown-skinned protagonist as white-knuckled. She pointed out in her line edits with a smiley face that that wasn’t possible. I remember being mildly embarrassed at not having caught the error. It would be our discussions with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o however, about the power of language in framing thought that would further drive home how that represented much more than an editorial oversight. It made me realize how much internal decolonizing and deprogramming I have to do, likely in ways I do not even fully understand, or have language for. It is of course ironic even now, that I can only pay tribute to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and his work in English. I realized in that moment and carry now, the knowledge that self-definition and a strong identity core, apart from the typecast roles of social stereotypes deeply matters. I am grateful for so many shoulders I stand on, from my parents, to African/Black scholars and writers like Nsamenang and wa Thiong’o, who have called me to hold on to African pride.

But most important is the reclamation of African languages. I have said that if you know all the languages of the world, and you don’t know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is enslavement; but if you know your mother tongue, or the language of your culture and add all the languages of the world to it, that is empowerment. Secure the base, our base, and then connect with the world. Securing our base, the base of our being, is what is assumed by the Afrocentric idea.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Afrocentrism Conference keynote, 2019

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o asked Africans everywhere: What is your story? What is our story? He and a generation of pan-Africans that raised these questions are passing the baton. The world around us is also seemingly at a threshold as we consider this fundamental question for humanity. What is our response? Who do we want to be? What will our answer be to future generations when it is our turn to transition to ancestors? I know that for Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the answer for Africans and people of African descent lies in first securing our own base, and then engaging the world as equals.

Afro-centrism should be driven by democratic logic: from our base we can connect with other people rooted in their basis, and even learn from them. In my book, Decolonizng the Mind, in the chapter titled, The Quest for Relevance, I have argued that what underlies the politics of language in African Literature is the search for a liberating perspective within which to see ourselves clearly in relationship to our selves and other selves in the universe…A secured Africa would be the base from which to launch ourselves to the highest of heights of human achievement. Wherever we go, wherever we are, in our work, in our bodies, in our names, in our intellect, in our advocacy, in how we carry ourselves, we should let that Africa shine with pride, an Africa, so secure in its base, that it is open to the best in other cultures on the basis of equal give and take.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Afrocentrism Conference keynote, 2019

Did we hear?

Did we listen?

Will we answer the call?

See full notes/speech by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o at the Afrocentrism Conference, 2019, here.